From Crisis to Liberation – Traces of a City Torn Apart

As we stood at the St. Nikolai Memorial during one of our tours, a participant once asked, “How could a city like Hamburg, full of music, trade, and Hanseatic tolerance, become a place of such destruction?” The question lingered in the air, echoing against the bomb-scarred tower that now stands as a monument of remembrance.

Hamburg’s story during World War II is not one of clear heroes and villains, but of a city struggling to survive under extreme circumstances. From the economic collapse of the 1930s to the oppression under Nazi rule, from the devastating firestorm that destroyed entire over 60% of the city, to the difficult years of rebuilding, Hamburg experienced the full impact of Germany’s darkest and most transformative decade.

Walking through its streets today, past memorial plaques, reconstructed buildings, and quiet Stolpersteine, we can still sense how the past breathes beneath the modern city. Understanding those traces helps us grasp how Hamburg fell, burned, and was reborn between 1929 and 1949.

The Great Depression and Hamburg’s Decline (1929–1933)

Hamburg was Germany’s largest port and Europe’s second busiest, after London. But when the 1929 stock market crash hit world trade, Hamburg suffered immensely. Exports fell, and industrial orders dried up. Unemployment skyrocketed: around 28 percent of Hamburg’s workforce was unemployed by 1932. In absolute terms, the number of unemployed soared from roughly 32,000 in 1928 to about 135,000 by 1932. Large working-class districts like Altona and St. Pauli saw acute hardship.

The great harbor, once vibrant, bore empty docks and stranded ships, a symbol of decline. Citizens faced hunger and poverty. Protests, bloody riots and even deadly revolts became common, as in many German cities. This hardship fueled political extremism. By 1932, the Nazi Party had become Hamburg’s largest party: it won 31,2 percent of votes in the April 1932 city elections, just above the Social Democrats’ 30,2 percent. Economic despair made many Hamburgers support the promise of radical change.

Nazi Seizure of Power – Hamburg Turns Brown (1933)

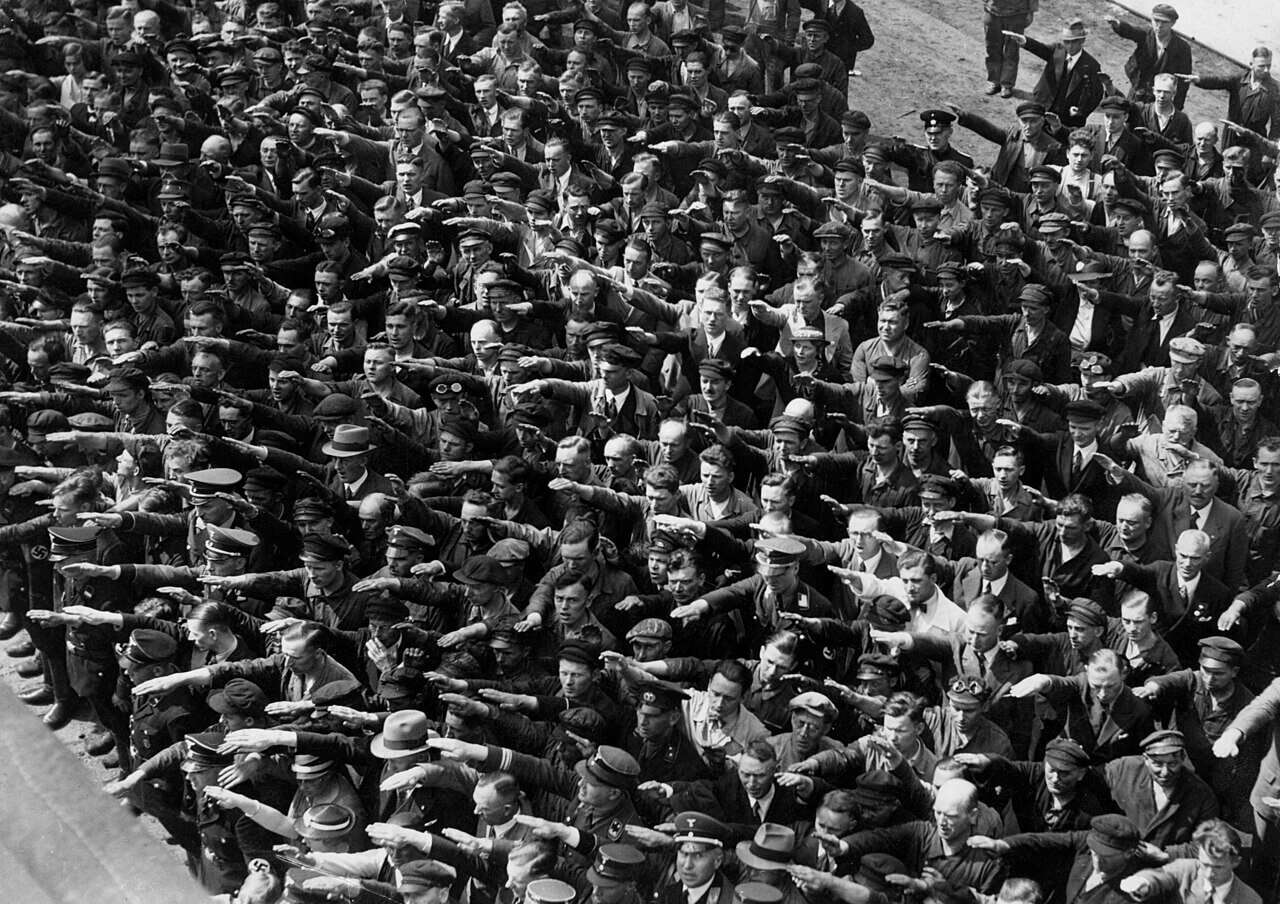

In 1933, after Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, the Nazis quickly consolidated control in Hamburg. They staged mass rallies, infiltrated the press and schools, and used new emergency powers to eliminate opposition. Following the Reichstag Fire Decree in February and the Enabling Act in March, political opponents were outlawed.

On March 3, 1933, SA units stormed Hamburg’s City Hall, seizing police and political offices. The following day, the then mayor of Hamburg Carl Wilhelm Petersen, resigned and on March 5th, 1933, the Nazi-Swastika was flown for the first time from the balcony of Hamburg’s town hall. SA leader, Karl Kaufmann, was soon installed as the city’s governor, ruling with near-dictatorial authority. The citizen elected Hamburg Parliament was dissolved, and a Nazi-dominated Senate assumed full control of the city as was justified by the then newly installed Nazi Parliamentary President: “The Senate is no longer accountable to the people”.

Repression followed almost immediately. The first Nazi arrest waves targeted Communists, Social Democrats, and trade unionists. In March 1933 alone, around 550 Hamburgers, mostly Communist leaders, were thrown into improvised jails. Old prisons and air-raid bunkers, such as the Stadtpark-Bunker and Fuhlsbüttel Prison, were turned into early concentration camps and torture sites. Fuhlsbüttel itself was converted into one of the regime’s first official camps by mid 1933. Local Nazi elites and industrialists quickly aligned with the new regime: major shipbuilders like Blohm+Voss and other firms benefited from early rearmament programs.

Everyday life changed rapidly. Nazi terror meant neighbors watched each other, and denunciations became routine. On April 1, 1933, SA men enforced a nationwide boycott of Jewish shops, humiliating Jewish business owners in Hamburg and across Germany. Hamburg’s Jewish community, one of the largest in the country, felt the new hostility immediately. Many families fled, while others were forced out in the years that followed.

Kristallnacht 1938 – A Turning Point of Violence

The Night of Broken Glass erupted on November 9th, 1938, unleashing a wave of terror that would forever scar Hamburg. Nazi hordes, fueled by hatred, smashed, burned, and shattered everything Jewish in their path. Shop windows exploded into deadly shards, synagogues blazed like torches in the night, and Jewish men, women, and children were beaten, humiliated, and dragged into the abyss. Hamburg’s grand Bornplatz Synagogue, a symbol of faith and community, was violated, defiled, but spared by the flames that night only to be torn down by Nazi hands soon after, its majestic stones reduced to rubble.

The streets ran with fear as Jewish families were ripped from their homes, their businesses looted, their lives shattered. This was no spontaneous rage, it was the first massive deportation, a calculated step toward annihilation. Thousands were herded like cattle, sent eastward into the unknown. Almost none came back.

Among them was Dr. Betty Warburg, a physician from one of Hamburg’s most respected families, torn from her life in 1943 and murdered in the Sobibor extermination camp. Rabbi Joseph Carlebach, the leader of Hamburg’s Jewish school, was deported to Latvia in 1943, he was executed by the Nazis, his voice silenced forever.

Today, Hamburg bears witness. Where the Bornplatz Synagogue once stood, Joseph-Carlebach-Platz now holds a mosaic of memory, tracing the outline of what was lost. And across the city, thousands of brass Stolpersteine, tiny, brass squares embedded in the pavement, whisper the names of the vanished. Each one a life. Each one a story erased by fire, by fury, by the machinery of genocide. Walk these streets, and you walk on their names. These are the scares the city remembers and can never undo.

Hamburg as a War Machine: Arms, Concentration Camps and Forced Labor (1939–1945)

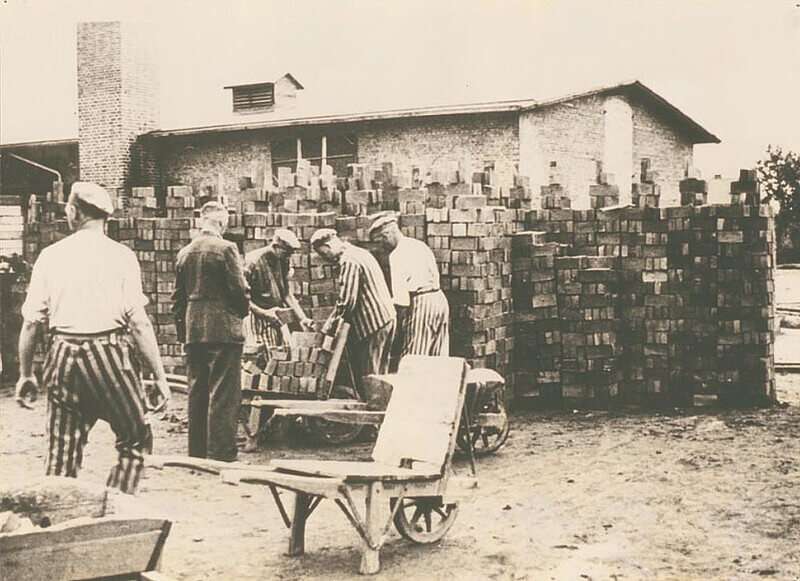

As war loomed in 1939, Hamburg’s industrial power was redirected toward weapons production. Hamburg’s darkest scar was Neuengamme, a concentration camp hidden just outside the city in Bergedorf. What began in late 1938 as a brutal labor camp soon sprawled into a monstrous network, its tendrils spreading across Hamburg through dozens of satellite camps. Over 100,000 people: political prisoners, resistance fighters, prisoners of war and Jews torn from their homes, were imprisoned within its barbed-wire confines. The Nazis had one purpose: exploitation until death. Forced to toil in brickworks and armaments factories, starved and broken, prisoners were worked to the bone, their bodies treated as nothing more than disposable tools.

The toll was unbearable. In the bitter winter of 1944–45, death claimed over 1,700 lives each month. By the war’s end, more than 50,000 men, women, and children had perished in Neuengamme’s grip—erased by hunger, disease, and the SS’s relentless cruelty.

Krystyna Razińska, one of the few who survived, later whispered of her ordeal: “God, how did I endure it all? The lice gnawing at my skin, the blood boils oozing with infection, the gnawing hunger, the beatings that left me gasping, the abuse that stripped me of my humanity. I was nothing but a shadow… hollow, unrecognizable. Perhaps I lived only because I was young, because my body had not yet been fully consumed by their evil.”

Shipyards such as Blohm+Voss, known for building the battleship Bismarck, shifted to mass-producing U-boats. Aircraft factories like Hamburger Flugzeugbau expanded rapidly, and munitions works such as Dynamit Nobel produced bombs around the clock. Every industry needed workers, yet millions of German men were serving in the army. To fill the gap, factories began importing forced laborers from occupied countries and prisoners of war on a vast scale. By 1944, approximately 500,000 foreign forced laborers and deportees were working in Hamburg’s industries. Many of these forced laborers lived in camps on the outskirts of the city. Blohm+Voss, for example, operated a camp in Steinwerder from July 1944 to April 1945.

Around five hundred mainly foreign women were imprisoned there, forced to work on warships under brutal conditions. At the Deutsche Werft shipyard in Finkenwerder, a massive U-boat bunker called Fink II was constructed between 1940 and 1942. This site also relied on forced labor, and in October 1944 a concentration camp satellite was established there. Hundreds of prisoners died from starvation, exhaustion, and Allied air raids.

One of the most chilling examples of Nazi sadism were the atrocities committed at Bullenhäuser Damm here in Hamburg under the direction of a SS doctor. Twenty Jewish children, ten girls and ten boys, aged just five to twelve, were brought from Auschwitz to Hamburg. There, they were deliberately infected with tuberculosis as part of the Nazis’ twisted quest to “prove” the supposed inferiority of the Jewish race.

The children endured unimaginable suffering: coughing up blood, searing chest pains, relentless fevers, crippling weakness, and agonizing headaches. Their torment was not just physical but a calculated act of cruelty, as the SS doctor callously accepted the risk of their deaths in the name of his monstrous ideology.

As the war neared its end, the Nazis sought to erase their crimes. The children, along with their four devoted caretakers, were hung to death in the cellar of the building. A desperate attempt to silence the truth. The SS doctor even buried the results of his experiments, hoping to conceal his horrors forever. Decades later, by sheer chance, his crimes were uncovered.

In 1966, he was finally convicted of crimes against humanity. He spent the rest of his life behind bars, but no punishment could ever atone for the lives he destroyed or the innocence he stole. The children of Bullenhäuser Damm were more than victims; they were symbols of the Nazi regime’s depravity, their voices silenced but their memory a haunting testament to the depths of human evil.

Most of Hamburg’s population rarely confronted these realities. Many citizens benefitted from wartime employment, while Nazi propaganda downplayed or concealed the existence of the camps. Some neighborhoods looked away, even when camp watchtowers stood within sight of their homes. By the final months of the war, forced labor had become an ordinary feature of city life, an irony lost on those who only noticed the empty factory floors when Allied bombers finally brought production to a halt.

Neuengamme was not just a camp; it was a factory of suffering, a place where the Nazi regime perfected the art of destruction, body by body, life by life. The ruins of those years still echo with the silent screams of those who didn’t survive.

Operation Gomorrah 1943 – The Firestorm

From July 24 to August 3, 1943, Hamburg endured the worst air raids of World War II. Under Operation Gomorrah, hundreds of British Royal Air Force bombers attacked by night, while hundreds of American bombers struck by day. British crews carpet-bombed densely populated districts with incendiary bombs, and American bombers focused their attacks on the port and ball-bearing factories during daylight hours. The combined effect created a firestorm, with overlapping fires merging into hurricane-strength winds of flame.

The destruction was catastrophic. Estimates suggest that between 35,000 and 40,000 people died, more than in any other German city bombing during the war. A memorial plaque near the Hammerbrook canal records that more than 35,000 people perished in the fires, including thousands of foreign forced laborers and over 5,000 children.

About one million Hamburg residents fled their homes in panic or were evacuated. There are stories of beer trucks driving relentlessly non-stop in and out of the city, evacuating civilians a dozen or so at a time. One survivor that came along on our tour recalled how she, a little girl at the time, spent three days in an overcrowded bunker before she was evacuated, saving her life as on the fourth night, everyone in the bunker was suffocated or roasted to death by the fire storm. By the end of the raids, entire neighborhoods such as Hammerbrook, Rothenburgsort, Horn, and Hamm in East Hamburg were almost completely destroyed by the firestorm.

Survivors woke on July 25 to see a thick orange glow hanging over the city and to breathe endless smoke. One diary described how by dawn the air was choked with embers, and survivors clawed through rubble searching for loved ones. In the following days, fire department crews, soldiers, and even prisoners from Neuengamme held in newly built local camps were forced to rescue trapped people, clear debris and chard corpses, and defuse unexploded bombs. The Hamburg firestorm left the city physically shattered and its population deeply traumatized.

Today, plaques and memorials mark the suffering endured during those days. At the main railway station, a plaque reminds visitors of Operation Gomorrah and its victims. In Ohlsdorf Cemetery, mass graves hold tens of thousands of the dead, their silent tombstones serving as somber reminders of the firestorm.

Liberation 1945 – Between Hope and Chaos

In early May 1945, with Nazi Germany collapsing, Allied forces finally closed in on Hamburg. After some last fighting, the city’s Nazi regime surrendered on May 3, 1945.

British troops marched in, greeted by a mix of relief and guilt. Many Hamburgers were astonished and asked themselves whether this was victory or defeat. Food was scarce, shelters were cold, and the city was still smoldering.

In the chaotic postwar months, daily life was a struggle. A black market flourished because official rations, often less than sixteen hundred calories per day, could not feed families. Women, known as the “Trümmerfrauen” (rubble women), cleared miles of rubble by hand to make way for reconstruction. The winter of 1946 to 1947 was harsh, with fog of debris, meager coal supplies, and populations suffering from hunger.

The occupying forces began denazification. Nazi propaganda books were banned, organizations were dissolved, and top figures were put on trial. In Hamburg, one symbolic case occurred when the Blohm+Voss shipyard directors Rudolf and Walther Blohm were brought before a British military tribunal in 1949 for trying to evade orders to dismantle the factory. Many lower-level officials faced similar tribunals in the late 1940s.

A New Beginning: From Rubble City to West Germany

By the 1950s, Hamburg was changing rapidly. Under the motto “We build rather than beg,” the city cleared ruins at a record pace. Business associations developed what became known as the Hamburger Modell of self-help, where workers and trade unions volunteered to clear streets on Fridays, paid for by industry, then returned to their jobs by Monday.

New housing was a crucial part of the recovery. The unions’ cooperative “Neue Heimat” became Europe’s largest non-profit housing builder, creating approximately 460,000 new apartments in West Germany between 1950 and 1982. Blocks of new housing rose in neighborhoods like Barmbek and Wandsbek, providing homes for war survivors.

Economically, Hamburg rebounded strongly as West Germany’s Gateway to the World. The port resumed shipping operations, and its coal, steel, and export industries expanded during the “Wirtschaftswunder”, or economic miracle. Hamburg also grew into a center of publishing and media. The newsweekly “Der Spiegel” was founded in 1947 and developed into one of Germany’s most influential news magazines. The city’s Chamber of Commerce and ship owners, now operating in a democratic framework, energetically drove the economic revival.

However, rebuilding was not only about physical reconstruction. The memory of the Nazi era emerged slowly. In the early postwar years, many Germans wanted to forget the horrors, which resulted in silent streets and little public discussion. By the 1960s, a new generation began to ask difficult questions. In 1965, former prisoners of the Neuengamme concentration camp erected an international memorial on the camp grounds, marking a turning point in public remembrance. Over time, exhibitions, plaques, and school programs helped fill gaps in knowledge. Hamburgers started gathering at important sites such as the ruined tower of St. Nikolai church and the memorial at Bornplatz to remember the crimes committed during the Nazi regime. During the 1960s and 1970s, trials of former SS guards and police officers, although few and delayed, forced the public to confront Hamburg’s past more openly.

By the early decades of the Federal Republic, Hamburg had firmly established itself as a federal state that emphasized democracy and local freedom. Its political leaders, including the prominent Mayor Helmut Schmidt, often warned that without remembering the National Socialist past, society risked repeating the same mistakes. Schmidt famously stated that whoever does not know the past cannot understand the present. The city’s “Rathaus”, or City Hall, even served as the seat of the British occupation government until 1949, symbolizing a democratic restart.

Today, many landmarks in Hamburg still bear the scars of war and remembrance. The empty spire of St. Nikolai’s church remains as a remembrance monument for air-raid victims. The former Neuengamme concentration camp has been transformed into a sprawling memorial museum. Institutions such as the Hamburg History Museum feature extensive exhibitions covering both the Nazi era and postwar Hamburg. Despite this, many streets and neighborhoods show no outward sign of their dark history, with silent corners marked only by Stolpersteine, small brass plaques embedded in the pavement that quietly commemorate the last chosen residences of those deported or murdered during the Nazi regime.

Hamburg’s Memory Culture Today

How does Hamburg remember World War II today? Across the city, museums such as the “Museum of Hamburg History” and the “Concentration Camp Memorial Neuengamme” host permanent exhibitions that ever remind us of history’s painful scars. Schools and public programs use local history to spark conversations about racism, refugees, and integration, showing that the past still speaks to present-day challenges.

Memory here is not always simple. Debates continued over how to handle former Nazi sites. For example, the “Budge Palaise”, a villa along the Alster lake owned by a jewish family that was confiscated by the Nazis and used as offices for the gauleiter of the Third Reich, reflecting the ongoing weight of history in daily life today. After the war, the city turned the building into the Conservatory for Music and Theater. However, a full restitution for the heirs of the Budge family wasn’t resolved until 2011. One thing remains clear though: remembering is a civic duty.

If you would like to discover Hamburg’s World War II history with us. Join our guided tours that bring this intense and complex past to life, walking through memorials, and neighborhoods marked by war and rebuilding. Explore the stories behind sites like the ruins of St. Nikolai, and understand how the city remembers those dark years. Whether you are a history enthusiast, a visitor seeking deeper understanding, or someone wanting to reflect on the echoes of war and renewal, we’re ready to guide you through Hamburg’s story of hardship and hope.

Join us on a private World War II Tour or Historic City Centre Free Tour, where we bring these powerful stories to life. Visit www.robinandthetourguides.de and let the journey begin.